Legends of the Victoria Falls (Part

2): The Place of the Rainbow

By Peter Roberts

The second part in a short series looking

at the cultural and natural history of the

The first article looked at the cultural traditions recorded by Livingstone on his visits to the Falls in 1855 and 1860 (available here). Now we look at how, fifty years later, the Victoria Falls were promoted to and perceived by early tourists, and how Livingstone himself now became part of the local legend of the Falls.

Part One available here:

Legends of the

Guiding

Spirits

In 1902 Mr Francis (Frank) William Sykes was appointed the first

Conservator of the Falls, responsible for the

The travel writer and correspondent for the London Morning Post, Mr Edward Frederick Knight, visited the Falls in early 1903, publishing a detailed account of his travels later the same year. Sykes guided Knight around the Falls, spending the first day exploring the north bank and the second day the south side.

Viewing the Falls from the Eastern Cataract Knight recorded his first impressions.

“It is too sublime a spectacle to have anything of

horror in it. The sense of danger is strangely absent as one looks from the

edge of the abyss at the majestic scene. It is as if one were out of this

universe and in some higher one where the forces of Nature are on a gigantic

scale, irresistible yet without menace; where there is no death or pain for

living things, so that they are able to gaze with a rapture of admiration

unmixed with fear at the stupendous and beautiful manifestations of power that

cannot hurt them. At the Victoria Falls the traveller feels that he might well

be looking on some landscape of

The next day they explored

the Falls from the south bank, and into the 'rainforest' (so named by the

German visitor,

At the western end of the Falls Knight recorded a tradition of tying the long grass into a knot as a 'petition to the spirits':

“We

followed the canon cliff round its westernmost curve, and I noticed that the

tufts of grass growing at the very brink of the abyss had been tied at the top

into knots by the natives, so that they had the appearance of so many ninepins.

Each of these knotted tufts was a petition to the spirits of the Falls, for the

Barotse feel the awful influence of the cataract, and in recognition of and in

supplication to the mystic power of the water they fashion these living

prayers.” (Knight, 1903,

p.349)

Sykes' knowledge of local

beliefs perhaps influenced Knight in his descriptions, particularly in relation

to the rainbows which follow the observer at close distance during certain

conditions in the dense atmosphere of the rainforest, and which Knight likened

to 'an attendant ghost,' an echo perhaps of the traditional cultural beliefs

associating the rainbow with the guiding spirits of the ancestors and the

resulting spiritual significance of the Falls (See: Legends of the

“Then we plunged into the Rain Forest itself, and here, though there were some open savannahs of grass and fern, the growth of trees and bush was generally so dense that we could only progress by following the many intersecting hippopotamus tracks, tunnels which these animals had forced through the vegetation, down which we had to crawl, wading through deep mud and rank sodden grass, and crossing many streams of running water made by the falling spray...

“It was a forest of eternal driving wind and rain; and yet, despite this, it was no dark, cheerless, stormy scene that surrounded us. We walked through an atmosphere that was bright and luminous and even dazzling to our eyes. For, from the cloudless blue above us, which we could not see, the fierce rays of the sun pierced the spray cloud, filling the air with a diffused watery ever-shifting light. It was as if the sunshine were pouring on us through a veil of thin white silk.

"In this light the raindrops on all the leaves sparkled like jewels. As we walked on there was always on the right hand of each of us a bright rainbow following him wheresoever he went like an attendant ghost. When we were in the more open spaces these rainbows retreated to a long distance off and waxed larger, appearing to span leagues of country; but when the forest closed in on us they came nearer and were smaller, in the denser jungle narrowing to arcs of colour not a yard across and so close that it seemed as if one had but to stretch out one's hand to touch them...

“And now that we were in the midst of the forest we realised all the unsurpassed luxuriance of this tropical vegetation bathed in sunshine and everlasting rain; the vivid greenness of the great trees, whose branches were linked with the multitudinous tendrils of the lianes and convolvuli; the lushness of the grass and ferns; the wondrous beauty of the various delicate flowers with rainbow-tinted petals, frail-looking but unharmed by the endless storm, marvellous blossoms that one was loth to pick. We plucked a few, hoping to keep them as specimens, but found that they almost immediately faded and withered in one's hand like the flowers of the enchanted garden of the fairy tale. And this might, indeed, have been a garden of fairyland, so unreal and dreamlike it looked in that luminous atmosphere...

“And yet ever by our side, advancing when we advanced, stopping when we stopped, were the faithful little attendant rainbows, brightening and waning with the changing density of the water-wind that swirled around us...

“And so on we went, drenched, for no waterproofs will keep one dry here, now under the dripping trees, now over the soaked savannahs, and now clambering over the slippery rocks on the cliff edge, until we had traversed the whole length of the Rain Forest and had come to the most terrible spot of all. We were standing at the extremity of that great wedge-shaped promontory of rock called Danger Point...

“We might have been gazing at a primordial chaos from which some day, after the passing of aeons, a world would be created. On this wild cape the air was no longer luminous, as in the forest; the sun’s rays did not pierce the dense vapours; the faithful little rainbows were unable to follow us here, and had left us.” (Knight, 1903, p.353-356)

The Place Where the Rain is Born

Fifty years after Livingstone's first visit to the Falls, Sykes authored the first ‘official’ tourism guide on the Falls, published during late August 1905. Sykes introduced his guide with the arrival of Dr Livingstone at the Falls in 1855, and records several local names and their meanings.

“The Native (Sekololo [Makalolo]) name for the Falls is Mosi-oa-Tunya, meaning ‘the smoke which sounds.’ It is a most appropriate one, as, viewed from any of the surrounding hills, this rising columns of spray, more particularly on a dull day, bear an extraordinary resemblance to the smoke of a distant veldt fire... The native in their songs say ‘how should anyone lose his way with such a land-mark to guide him?’” (Sykes, 1905)

On Livingstone Island Sykes wrote:

“Situated

on the edge of the chasm almost in the centre of the Falls is the

Of the Rainforest, first named by the German traveller Edward Mohr who visited in 1870, Sykes notes:

“The name is well chosen, for here it is always dripping. The natives themselves refer to it as 'the place where the rain is born.'” (Sykes, 1905)

At the end of the guide Sykes listed the regulations which visitors were expected to follow for the protection of the Falls environments, detailing the prohibiting of:

“- Shooting of any and every description within a radius of five miles [8 km] of the Falls on either bank.

- Netting and dynamiting in the river.

- The cutting of initials on or other defacement of

the boles of trees.

- Plucking of flowers and ferns, uprooting ferns,

orchids or other plants.

- Setting fire to the grass in the park.

- Trespassing of animals.

- Washing of clothes in the river above the Falls.

- Picnic parties are requested to remove all traces of their presence, such as tins, bottles, paper, etc, before leaving.

“The importance of the above will be obvious to all

visitors who are lovers of nature, and their loyal observance is confidently

relied upon.” (Sykes, 1905)

The regulations protecting the environment of the Falls not only protected the Falls and its immediate surrounds from the actions of indiscriminate visitors, but also limited access to, and the use of, the river and Falls for local Leya people, including access to sacred shrines and sites around the Falls - the prohibition of the washing of clothes in the river apparently directed specifically at the cleansing rituals carried out in the natural pools on the lip of the Falls.

A New Shrine

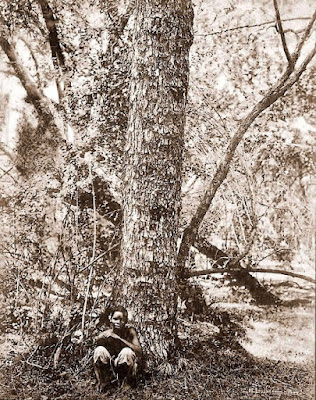

A few months previously, in late 1902, Sykes had visited Garden Island with a local elder, Namakabwa, who showed him the tree upon which Livingstone had carved his initials, and which were said to still be faintly visible. Sykes later recorded its rediscovery:

“The Name Tree upon which he cut his initials still remains. Its identity was determined two years ago by the writer... An old white-haired native, by name Namakabwa, who spent most of his time down the gorge catching fish, on being questioned said he well remembered Livingstone, whose native name was ‘Monari,’ coming to the Falls, and described how he (Namakabwa) a day or two after Livingstone’s departure, made his way over to the island and found that a small plot had been cleared of bushes, also that he had made some cutting on a tree. When asked ‘which tree?’ he immediately went to the Name Tree, and put his finger on what had evidently been a cut. The authenticity of the above then is based on the evidence of ‘the oldest inhabitant,’ and may be accepted as genuine. The bark of the tree is so rough and the marks so nearly obliterated that one would have had some doubts on the subject, were the source of information less worthy of belief.

“It is to be recorded with regret that a certain class of tourists, to whom nothing is sacred, had commenced to strip and carry away pieces of the bark from this tree, and so came the necessity for a notice-board and tree-guard, in themselves a witness against the relic hunting vandal who lightly destroys what can never be replaced. Even Livingstone, the discoverer of the Falls, excuses himself for ‘this piece of vanity.’ Would that others were only as sensitive on this point as the great explorer, and delay carving their meaningless initials on the trunks of trees until they can boast such a world-wide fame as was his to excuse the act!” (Sykes, 1905)

The railway line from

the south to the

Tours to

"The Livingstone

correspondent of the Bulawayo Chronicle states that the tree upon which Dr

Livingstone carved his initials at the Victoria Falls, is dying, and it is

proposed to cut down the trunk and send it to

When the now famous bronze statue of David Livingstone was unveiled overlooking the western view of the Falls in August 1934, news reports recorded Livingstone’s initials were apparently still faintly visible on the tree he had originally carved them into in 1855, although by now serious doubts were being expressed as to the authenticity of the marks and even the identification of the tree itself.

References

Knight, E. F. (1903)

Sykes, F. W. (1905)

Official Guide to the

News

from Barotsiland (1906) No.27, January 1906. p.8.

The sacred island sanctuary and protected wildlife refuge of Cataract Island is threatened by the recent launch of tourism tours and activities to the island, endangering not only its fragile ecology but also the wider status of the Falls as a World Heritage Site.

Read more:

- - -

Peter Roberts is an ecologist, conservationist and

freelance researcher and writer with a special focus on the

No comments:

Post a Comment