Legends of the Victoria Falls (Part 1):

Spirits of the Falls

By Peter Roberts

This short feature looks at the local

cultural traditions and beliefs recorded by Dr David Livingstone and other

early travellers to the Victoria Falls - although the records of outsiders to

the region, they are the earliest written records which we have of these

'Spirits of the Falls' and important insights into the sacred island shrines on the lip of the Falls - cultural sites which are today largely forgotten.

Part Two now online:

Legends of the Victoria Falls (Part 2): Place of the Rainbow.

- - -

A Journey Downstream

On 16th November 1855

David Livingstone was being escorted down the Zambezi

River by Chief Sekeletu, accompanied

by some 200 Makalolo assistants, on his way to the east coast of Africa and the completion of his epic transverse of the

continent from west to east coast.

Travelling downstream,

Livingstone was told of local belief in a river spirit-serpent (widespread

across central Africa):

“The Barotse believe that at a certain part of the

river a tremendous monster lies hid, that will catch a canoe and hold it

motionless in spite of the efforts of the paddlers. They believe that some of

them possess the knowledge of the proper prayer to lay the monster.”

(Livingstone, 1857, p.517)

Livingstone described the

journey in detail, made both by boat and also walking along the north bank in

sections to avoid the rapids, downstream to Kalai Island,

about 10 kilometres above the Falls.

“Having descended about ten miles [16 km], we came

to the island of Nampene, at the beginning of the

[Katambora] rapids, where we were obliged to leave the canoes and proceed along

the banks on foot. The next evening we slept opposite the island of Chondo,

and... early the following morning were at the island of Sekote,

called Kalai. This Sekote was the last of the Batoka chiefs whom Sebituane

rooted out... Most of his people were slain or taken captive, and the island

has ever since been under the Makololo. It is large enough to contain a

considerable town.

“On the northern side I found the kotla

[fortress/palace] of the elder Sekote, garnished with numbers of human skulls

mounted on poles: a large heap of the crania of hippopotami, the tusks

untouched except by time, stood on one side. At a short distance, under some

trees, we saw the grave of Sekote, ornamented with seventy large elephants’

tusks planted round it with the points turned inward, and there were thirty

more placed over the resting-places of his relatives.” (Livingstone, 1857,

p.517-8)

Mosi-oa-Tunya

Livingstone had little

idea of what lay ahead, other than a note on a rough map he had prepared on his

first visit to the Zambezi in 1851: “Waterfall of Sikota - called Mosi-ia-thunya

or smoke sounds (spray can be seen 10 miles distance).”

In mid-1851 Livingstone

and his travelling companion William Oswell had explored north into the

unmapped interior, eventually reaching a large river which Livingstone

correctly identified as the Zambezi, and previously

known only to Europeans by its lower stretches and great delta on the east

coast.

Befriending the Makalolo

Chief, Sebetwane, who held power in the region, they were told of a great

waterfall some distance downstream, although they did not travel to visit them

on this occasion. Livingstone later recorded:

“Of these we had often heard since we came into the

country; indeed, one of the questions asked by Sebituane [in 1851] was, ‘Have

you smoke that sounds in your country?’ They [the Makalolo] did not go near

enough to examine them, but, viewing them with awe at a distance, said, in

reference to the vapour and noise, ‘Mosi oa Tunya’ (smoke does sound there). It

was previously called Shongwe, the meaning of which I could not ascertain. The

word for a 'pot' resembles this, and it may mean a seething caldron; but I am

not certain of it.” (Livingstone, 1857, p.518)

In fact Livingstone had

spent the following years exploring in every other direction, before

eventually, in late 1855 he set off downstream with Sekeletu (Sebetwane's

successor) and his Makalolo companions for the east coast.

The rising spray at dawn (Photo Credit: Peter Roberts)

Scenes so Lovely

Guided to the Falls by a

local Leya boatman, Livingstone was enchanted by the beauty of the wide, island

studded Zambezi River, its forested fringes and exotic

wildlife

"After twenty minutes' sail from Kalai we came

in sight, for the first time, of the columns of vapor appropriately called

'smoke,' rising at a distance of five or six miles, exactly as when large

tracts of grass are burned in Africa. Five columns now arose, and, bending in

the direction of the wind, they seemed placed against a low ridge covered with

trees; the tops of the columns at this distance appeared to mingle with the

clouds. They were white below, and higher up became dark, so as to simulate

smoke very closely. The whole scene was extremely beautiful. The banks and

islands dotted over the river are adorned with sylvan vegetation of great

variety of color and form. At the period of our visit several trees were

spangled over with blossoms. Trees have each their own physiognomy. There,

towering over all, stands the great burly baobab, each of whose enormous arms

would form the trunk of a large tree, besides groups of graceful palms, which,

with their feathery-shaped leaves depicted on the sky, lend their beauty to the

scene...; but no one can imagine the beauty of the view from any thing

witnessed in England.

It had never been seen before by European eyes; but scenes so lovely must have

been gazed upon by angels in their flight.” (Livingstone, 1857, p.519)

This last passage has

often been misquoted in reference to the Falls themselves, but it was the

stretches of the river upstream which first captured Livingstone’s imagination.

Livingstone was guided to

a small island on the very lip of the Falls. Scrambling through vegetation to

the sudden edge Livingstone struggled to understand the scene which lay before

him:

“I did not comprehend it until, creeping with awe

to the verge, I peered down into a large rent which had been made from bank to

bank of the broad Zambesi, and saw that a stream of a thousand yards [915 m]

broad leaped down a hundred feet [30.5 m], and then became suddenly compressed

into a space of fifteen or twenty yards. The entire Falls are simply a crack

made in a hard basaltic rock from the right to the left bank of the Zambesi,

and then prolonged from the left bank away through thirty or forty miles of

hills... the most wonderful sight I had witnessed in Africa.” (Livingstone,

1857, p.520)

Livingstone was perhaps

deliberately cautious in his estimates, adding: “Whoever may come after me will not, I trust, have reason to say I have

indulged in exaggeration.” He seriously underestimated the scale of the Falls,

which span 1,708 metres (5,604 feet or 1,868 yards) and drop up to 108 metres

(355 feet).

Of the Falls he would

later write that it “is a rather hopeless task to endeavour to convey an

idea of it in words” (Livingstone and Livingstone, 1865, p.252).

Above the Falls, seen from Livingstone Island (Photo Credit: Peter Roberts)

Sacred Island Shrines

On this first visit

Livingstone recorded that three sites at the Falls were used by the three local

Leya chiefs for offerings to the ‘Barimo,’ but identifies only one of these

sites - now known as Livingstone Island, recording the following in his

'Missionary Travels' on his first arrival and sight of the Falls from this

island on its very edge.

“At three spots near these Falls, one of them the

island in the middle, on which we were, three Batoka chiefs offered up prayers

and sacrifices to the Barimo. They chose their places of prayer within the

sound of the roar of the cataract, and in sight of the bright bows in the

cloud.

“They must have looked upon the scene with awe. Fear

may have induced the selection. The river itself is to them mysterious.

“The words of the canoe-song are,

"The

Leeambye! Nobody knows

Whence it

comes and whither it goes..."

“The play of colors of the double iris on the

cloud, seen by them elsewhere only as the rainbow, may have led them to the

idea that this was the abode of Deity. Some of the Makololo... looked upon the

same sign with awe. When seen in the heavens it is named 'motse oa barimo' -

the pestle of the gods.

“Here they could approach the emblem, and see it

stand steadily above the blustering uproar below - a type of Him who sits

supreme - alone unchangeable, though ruling over all changing things. But, not

aware of His true character, they had no admiration of the beautiful and good

in their bosoms. They did not imitate His benevolence, for they were a bloody,

imperious crew, and Sebituane performed a noble service in the expulsion from

their fastnesses of these cruel 'Lords of the Isles' [Sekute and the other Leya chiefs]

“Having feasted my eyes long on the beautiful

sight, I returned to my friends at Kalai, and saying to Sekeletu that he had

nothing else worth showing in his country, his curiosity was excited to visit

it the next day." (Livingstone, 1857, p.523-4)

To the local Leya this

island was known as Kazeruka, whilst the first Conservator of the Falls, F W

Sykes, later recorded that it was also known as Kempongo, meaning 'Goat' Island

(Sykes, 1905).

View from the Western or Devil's Cataract (Photo Credit: Peter Roberts)

Guiding Spirits

Livingstone had earlier

expanded on the concept of the Barimo, which he interpreted as the 'gods or

departed spirits' and its relationship to the rainbow, as recorded when

witnessing a solar halo.

“Another incident, which occurred at the confluence

of the Leeba and Leeambye, may be mentioned here, as showing a more vivid

perception of the existence of spiritual beings, and greater proneness to

worship, than among the Bechuanas. Having taken lunar observations in the morning,

I was waiting for a meridian altitude of the sun for the latitude; my chief

boatman was sitting by, in order to pack up the instruments as soon as I had

finished; there was a large halo, about 20° in diameter, round the sun;

thinking that the humidity of the atmosphere, which this indicated, might

betoken rain, I asked him if his experience did not lead him to the same view.

‘Oh, no,’ replied he; ‘it is the Barimo (gods or departed spirits), who have

called a picho [meeting]; don’t you see they have the Lord (sun) in the

centre?’” (Livingstone, 1857, p.121)

Livingstone documented

many references to the Barimo during his travels, identifying a common tradition widespread across the regions north of the Zambezi.

“The same superstitious ideas being prevalent

through the whole of the country north of the Zambesi, seems to indicate that

the people must originally have been one. All believe that the souls of the

departed still mingle among the living, and partake in some way of the food

they consume. In sickness, sacrifices of fowls and goats are made to appease

the spirits. It is imagined that they wish to take the living away from earth

and all its enjoyments. When one man has killed another, a sacrifice is made,

as if to lay the spirit of the victim. A sect is reported to exist, who kill

men in order to take their hearts and offer them to the Barimo."

(Livingstone, 1857, p.434)

When he finally reached

the east coast in April 1856, Livingstone met a Portuguese official who appears

to expand on various native names for Livingstone's Barimo and the traditional

beliefs of the Zambezi

Valley - but reminding us

of several centuries of Christian Portuguese influence from both east and west

coasts of the continent.

“As Senhor Candido holds the office of judge in all

the disputes of the natives and knows their language perfectly, his statement

may be relied on that all the natives of this region have a clear idea of a

Supreme Being, the maker and governor of all things. He is named 'Morimo,'

'Molungo,' 'Keza,' 'Mpambe,' in the different dialects spoken. The Barotse name

him 'Nyampi,' and the Balonda 'Zambi.' All promptly acknowledge him as the

ruler over all. They also fully believe in the soul's continued existence apart

from the body, and visit the graves of relatives, making offerings of food,

beer, &c When undergoing the ordeal, they hold up their hands to the Ruler

of Heaven, as if appealing to him to assert their innocence. When they escape,

or recover from sickness, or are delivered from any danger, they offer a sacrifice

of a fowl or a sheep, pouring out the blood as a libation to the soul of some

departed relative. They believe in the transmigration of souls; and also that

while persons are still living they may enter into lions and alligators, and

then return again to their own bodies." (Livingstone, 1857, p.641-2)

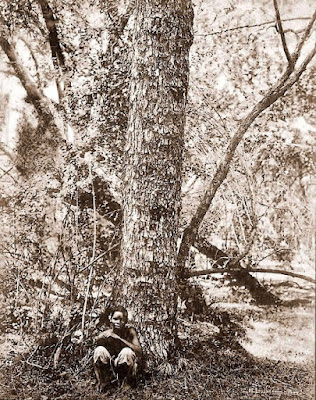

Nature's Nursery

Livingstone returned to

the island the following day in the company of Sekeletu and several Makalolo.

"Sekeletu acknowledged to feeling a little

nervous at the probability of being sucked into the gulf before reaching the

island. His companions amused themselves by throwing stones down, and wondered

to see them diminishing in size, and even disappearing, before they reached the

water at the bottom." (Livingstone, 1857, p.524)

Livingstone spent most of

this second day planting and garden of coffee and fruit trees which he hoped

would grow under the spray of the Falls.

"I had another object in view in my return to

the island. I observed that it was covered with trees, the seeds of which had

probably come down with the stream from the distant north, and several of which

I had seen nowhere else, and every now and then the wind wafted a little of the

condensed vapor over it, and kept the soil in a state of moisture, which caused

a sward of grass, growing as green as on an English lawn. I selected a spot -

not too near the chasm... but somewhat back, and made a little garden. I there

planted about a hundred peach and apricot stones, and a quantity of

coffee-seeds. I had attempted fruit-trees before, but... they were always

allowed, to wither, after having vegetated, by being forgotten. I bargained for

a hedge with one of the Makololo, and if he is faithful, I have great hopes of

Mosi-oa-tunya’s abilities as a nurseryman. My only source of fear is the

hippopotami. When the garden was prepared, I cut my initials on a tree, and the

date 1855. This was the only instance in which I indulged in this piece of

vanity. The garden stands in front, and were there no hippopotami, I have no

doubt but this will be the parent of all the gardens, which may yet be in this

new country.” (Livingstone, 1857, p.524-5)

Fortunately Livingstone's

garden of non-native trees did not grow, the hippopotami doing their job as

nature's caretakers made sure of that - although one can only wonder what the

Leya thought of his 'cultivation' of their sacred island shrine. It is

interesting to note that Livingstone specifically mentions hiring a Makalolo

'gardener' to tend the island, rather than one of the local Leya - his Leya

boatmen presumably having nothing to do with this enterprise.

Today conservationists and

ecologists would also frown at the thought of planting non native species in

such a pristine natural wilderness (and indeed great amounts of effort every

year go into controlling 'alien' invasive species such as Lantana) - and ugly the carving of initials into the bark of trees

is also rightly to be discouraged.

View from Western End showing glimpse of Main Falls (Photo Credit: Peter Roberts)

Return to the Falls

Livingstone returned to

the Falls in 1860, revising his translation of the traditional name:

"Mosi-oa-tunya is the Makololo name, and means

smoke sounding; Seongo or Chongwe, meaning the Rainbow, or the place of the

Rainbow, was the more ancient term they bore." (Livingstone and

Livingstone, 1865, p.250)

On this visit he recorded

that both the islands along the edge of the Falls were used for traditional

ceremonies and as a place of spiritual offering and respect. Cataract Island,

also known by its traditional name of Boaruka (or Boruka) Island, signifying

'divider of the waters,' is the second and larger of the two islands which line

the Falls, and is located at the western end of the Falls, dividing the Devil's

Cataract from the Main Falls.

"The sunshine, elsewhere in this land so

overpowering, never penetrates the deep gloom of that shade [in the rainforest]. In the presence of the strange Mosi-oa-tunya,

we can sympathize with those who, when the world was young, peopled earth, air,

and river, with beings not of mortal form. Sacred to what deity would be this

awful chasm and that dark grove, over which hovers an ever-abiding 'pillar of

cloud'?

“The ancient Batoka chieftains used Kazeruka, now Garden Island,

and Boaruka, the island further west, also on the lip of the Falls, as sacred

spots for worshipping the Deity. It is no wonder that under the cloudy columns,

and near the brilliant rainbows, with the ceaseless roar of the cataract, with

the perpetual flow, as if pouring forth from the hand of the Almighty, their

souls should be filled with reverential awe. It inspired wonder in the native

mind throughout the interior.” (Livingstone and Livingstone, 1865, p.258)

Livingstone again planted

out a garden on the island, noting that the care of trees was a 'civilizing

influence.'

“The hippopotami had destroyed the trees which were

then planted; and, though a strong stockaded hedge was made again, and living

orange-trees, cashew-nuts, and coffee seeds put in afresh, we fear that the

perseverance of the hippopotami will overcome the obstacle of the hedge. It would require a resident missionary to rear

European fruit-trees. The period at

which the peach and apricot come into blossom is about the end of the dry

season, and artificial irrigation is necessary... When a tribe takes an interest

in trees, it becomes more attached to the spot on which they are planted, and

they prove one of the civilizing influences.” (Livingstone and Livingstone,

1865. p.259-60)

Despite the failure of

these attempts, the island became widely known as Garden Island

and a popular destination for early European visitors to the Falls, with

several of those that followed in Livingstone's footsteps visiting the island

and adding their initials to the 'Livingstone Tree.'

Livingstone again later

repeated the cultural association between the rainbow and departed spirits.

“The rainbow, in some parts, is called the 'pestle

of the Barimo.'” (Livingstone and

Livingstone, 1865, p.542)

It is clear Livingstone

identified a widespread cultural belief across the region associating the

rainbow with the spirits of the departed ancestors (a variation of a common

theme in many cultures), and no doubt the Falls, where the rainbows daily play

across the mists of the spray, thus held special significance for the local

Leya. It is also evident, from the writings of Livingstone and others, that the

islands along the line of the Falls, played a central role in this cultural reverence.

The French Christian

missionary François Coillard, who visited the Falls in 1878, recorded:

“One can scarcely gaze into these depths for a moment,

or follow for an instant the tortuous and restricted current of this river,

without turning giddy. The beholder's first impression is one of terror. The

natives believe it is haunted by a malevolent and cruel divinity, and they make

it offerings to conciliate its favour, a bead necklace, a bracelet, or some

other object, which they fling into the abyss, bursting into lugubrious

incantations, quite in harmony with their dread and horror.” (Coillard, 1897

p.55)

Catherine Winkworth

Mackintosh, Coillard's niece, travelled to the Falls in late August 1903 and

recorded:

“At the edge of the cliff... the long grass was

knotted into bunches, an act of prayer or thanksgiving for a safe journey on

the part of numerous natives towards the Spirit of the Falls.” (Mackintosh,

1922, p.71)

References

Coillard, F. (1897) On the

threshold of Africa - A Record of Twenty Years Pioneering among the Barotse of

the Upper Zambezi. Hodder and Stoughton,

London. Download pdf (opens in new window)

Livingstone, D. (1857)

Missionary travels and researches in South Africa. London. Download pdf.

Livingstone, D. and

Livingstone, C. (1865) Narrative of an expedition to the Zambesi and its

tributaries and of the discovery of the lakes Shirwa and Nyassa, 1858-1864.

John Murray, London. Download pdf.

Mackintosh, C. W. (1922)

The New Zambesi Trail ; a record of two journeys to North-Western Rhodesia

(1903 and 1920). Unwin, London. Download pdf.

Sykes, F. W. (1905)

Official Guide to the Victoria

Falls. Argus Co., Bulawayo.

- - -

Peter Roberts is an ecologist, conservationist and

freelance researcher and writer with a special focus on the Victoria

Falls region. He is author of several books on the history of the

Falls, including 'Footsteps Through Time - a history of Travel and Tourism to the

Victoria Falls' [First published in July 2017, revised third edition April

2021]. See the Zambezi Book Company website for more information.

- - -

Cataract Island Under Threat of Tourism Development

The sacred island sanctuary and protected wildlife refuge of Cataract Island is threatened by the recent launch of tourism tours and activities to the island, endangering not only its fragile ecology but also the wider status of the Falls as a World Heritage Site.

Read more: Fears Grow Over Falls World Heritage Status

UPDATE: Online petition launched: Keep Victoria Falls Wild - Stop commercialization of Cataract Island and Surrounding majestic wild areas (Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe). Please sign and share...