Legends of the Victoria Falls (Part

2): The Place of the Rainbow

By Peter Roberts

The second part in a short series looking

at the cultural and natural history of the Victoria Falls,

a natural wonder of the world and UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The first article looked at the cultural traditions

recorded by Livingstone on his visits to the Falls in 1855 and 1860 (available here). Now we

look at how, fifty years later, the Victoria Falls were promoted to and perceived by

early tourists, and how Livingstone himself now became part of the local legend

of the Falls.

Part One available here:

Legends of the Victoria Falls (Part 1): Spirits of the Falls.

Victoria falls viewed from western end, Cataract Island in foreground

(Photo Credit: Peter Roberts)

Guiding

Spirits

In 1902 Mr Francis (Frank) William Sykes was appointed the first

Conservator of the Falls, responsible for the Falls Park

established on both sides of the river around the immediate area of the Falls

for a distance of five miles. Sykes appears to have spent some time trying to

understand the local traditions and cultural beliefs surrounding the Falls.

The travel writer and

correspondent for the London Morning Post, Mr Edward Frederick Knight, visited

the Falls in early 1903, publishing a detailed account of his travels later the

same year. Sykes guided Knight around the Falls, spending the first day

exploring the north bank and the second day the south side.

Viewing the Falls from the

Eastern Cataract Knight recorded his first impressions.

“It is too sublime a spectacle to have anything of

horror in it. The sense of danger is strangely absent as one looks from the

edge of the abyss at the majestic scene. It is as if one were out of this

universe and in some higher one where the forces of Nature are on a gigantic

scale, irresistible yet without menace; where there is no death or pain for

living things, so that they are able to gaze with a rapture of admiration

unmixed with fear at the stupendous and beautiful manifestations of power that

cannot hurt them. At the Victoria Falls the traveller feels that he might well

be looking on some landscape of Paradise.”

(Knight, 1903, p.344)

The next day they explored

the Falls from the south bank, and into the 'rainforest' (so named by the

German visitor, E Mohr in 1870) opposite the

main falls.

At the western end of

the Falls Knight recorded a tradition of tying the long grass into a knot as a

'petition to the spirits':

“We

followed the canon cliff round its westernmost curve, and I noticed that the

tufts of grass growing at the very brink of the abyss had been tied at the top

into knots by the natives, so that they had the appearance of so many ninepins.

Each of these knotted tufts was a petition to the spirits of the Falls, for the

Barotse feel the awful influence of the cataract, and in recognition of and in

supplication to the mystic power of the water they fashion these living

prayers.” (Knight, 1903,

p.349)

Sykes' knowledge of local

beliefs perhaps influenced Knight in his descriptions, particularly in relation

to the rainbows which follow the observer at close distance during certain

conditions in the dense atmosphere of the rainforest, and which Knight likened

to 'an attendant ghost,' an echo perhaps of the traditional cultural beliefs

associating the rainbow with the guiding spirits of the ancestors and the

resulting spiritual significance of the Falls (See: Legends of the Victoria Falls (Part 1): Spirits of the Falls).

“Then we

plunged into the Rain Forest itself, and here, though there were some open

savannahs of grass and fern, the growth of trees and bush was generally so

dense that we could only progress by following the many intersecting

hippopotamus tracks, tunnels which these animals had forced through the

vegetation, down which we had to crawl, wading through deep mud and rank sodden

grass, and crossing many streams of running water made by the falling spray...

“It was

a forest of eternal driving wind and rain; and yet, despite this, it was no

dark, cheerless, stormy scene that surrounded us. We walked through an

atmosphere that was bright and luminous and even dazzling to our eyes. For,

from the cloudless blue above us, which we could not see, the fierce rays of

the sun pierced the spray cloud, filling the air with a diffused watery

ever-shifting light. It was as if the sunshine were pouring on us through a

veil of thin white silk.

Viewed through the rainforest (Photo Credit: Peter Roberts)

"In this light the raindrops on all the leaves

sparkled like jewels. As we walked on there was always on the right hand of

each of us a bright rainbow following him wheresoever he went like an attendant

ghost. When we were in the more open spaces these rainbows retreated to a long

distance off and waxed larger, appearing to span leagues of country; but when

the forest closed in on us they came nearer and were smaller, in the denser

jungle narrowing to arcs of colour not a yard across and so close that it

seemed as if one had but to stretch out one's hand to touch them...

“And now

that we were in the midst of the forest we realised all the unsurpassed

luxuriance of this tropical vegetation bathed in sunshine and everlasting rain;

the vivid greenness of the great trees, whose branches were linked with the

multitudinous tendrils of the lianes and convolvuli; the lushness of the grass

and ferns; the wondrous beauty of the various delicate flowers with

rainbow-tinted petals, frail-looking but unharmed by the endless storm, marvellous

blossoms that one was loth to pick. We plucked a few, hoping to keep them as

specimens, but found that they almost immediately faded and withered in one's

hand like the flowers of the enchanted garden of the fairy tale. And this

might, indeed, have been a garden of fairyland, so unreal and dreamlike it

looked in that luminous atmosphere...

“And yet

ever by our side, advancing when we advanced, stopping when we stopped, were

the faithful little attendant rainbows, brightening and waning with the changing

density of the water-wind that swirled around us...

“And so

on we went, drenched, for no waterproofs will keep one dry here, now under the

dripping trees, now over the soaked savannahs, and now clambering over the

slippery rocks on the cliff edge, until we had traversed the whole length of

the Rain Forest and had come to the most terrible spot of all. We were standing

at the extremity of that great wedge-shaped promontory of rock called Danger

Point...

“We might have been gazing at a primordial chaos

from which some day, after the passing of aeons, a world would be created. On

this wild cape the air was no longer luminous, as in the forest; the sun’s rays

did not pierce the dense vapours; the faithful little rainbows were unable to

follow us here, and had left us.” (Knight, 1903, p.353-356)

The

Place Where the Rain is Born

Fifty years after Livingstone's first visit to the

Falls, Sykes authored the first ‘official’ tourism guide on the Falls, published

during late August 1905. Sykes introduced his guide with the arrival of Dr

Livingstone at the Falls in 1855, and records several local names and their

meanings.

“The Native (Sekololo [Makalolo]) name for the

Falls is Mosi-oa-Tunya, meaning ‘the smoke which sounds.’ It is a most

appropriate one, as, viewed from any of the surrounding hills, this rising

columns of spray, more particularly on a dull day, bear an extraordinary

resemblance to the smoke of a distant veldt fire... The native in their songs say

‘how should anyone lose his way with such a land-mark to guide him?’” (Sykes,

1905)

Cataract Island is given its now commonly used English name, with

Boruka as “the native name, signifying

‘divider of the waters.’”

On

Livingstone Island Sykes wrote:

“Situated

on the edge of the chasm almost in the centre of the Falls is the Island named after David Livingstone. ‘Kempongo’ was the

old native name, which means ‘Goat Island.’ He

himself named it Garden

Island. It is a curious

coincidence that it should bear a similar name to that other island which

occupies almost an identical position at Niagara.”

(Sykes, 1905)

Of

the Rainforest, first named by the German traveller Edward Mohr who visited in

1870, Sykes notes:

“The

name is well chosen, for here it is always dripping. The natives themselves

refer to it as 'the place where the rain is born.'” (Sykes, 1905)

Cataract Island (Photo Credit: Peter Roberts)

At the end of the guide

Sykes listed the regulations which visitors were expected to follow for the

protection of the Falls environments, detailing the prohibiting of:

“- Shooting of any and every description within a

radius of five miles [8 km] of the Falls

on either bank.

- Netting and dynamiting in the river.

- The cutting of initials on or other defacement of

the boles of trees.

- Plucking of flowers and ferns, uprooting ferns,

orchids or other plants.

- Setting fire to the grass in the park.

- Trespassing of animals.

- Washing of clothes in the river above the Falls.

- Picnic parties are requested to remove all traces

of their presence, such as tins,

bottles, paper, etc, before leaving.

“The importance of the above will be obvious to all

visitors who are lovers of nature, and their loyal observance is confidently

relied upon.” (Sykes, 1905)

The regulations protecting

the environment of the Falls not only protected the Falls and its immediate

surrounds from the actions of indiscriminate visitors, but also limited access

to, and the use of, the river and Falls for local Leya people, including access to sacred shrines and sites around the Falls - the prohibition of the washing of clothes in the river apparently directed specifically at the cleansing rituals carried out in the natural pools on the lip of the Falls.

A New

Shrine

A few months previously, in

late 1902, Sykes had visited Garden Island with a local elder, Namakabwa, who

showed him the tree upon which Livingstone had carved his initials, and which

were said to still be faintly visible. Sykes later recorded its rediscovery:

“The Name Tree upon which he cut his initials still

remains. Its identity was determined two years ago by the writer... An old

white-haired native, by name Namakabwa, who spent most of his

time down the gorge catching fish, on being questioned said he well remembered

Livingstone, whose native name was ‘Monari,’ coming to the Falls, and described

how he (Namakabwa) a day or two after Livingstone’s departure, made his way

over to the island and found that a small plot had been cleared of bushes, also

that he had made some cutting on a tree. When asked ‘which tree?’ he

immediately went to the Name Tree, and put his finger on what had evidently

been a cut. The authenticity of the above then is based on the evidence of ‘the

oldest inhabitant,’ and may be accepted as genuine. The bark of the tree is so

rough and the marks so nearly obliterated that one would have had some doubts

on the subject, were the source of information less worthy of belief.

“It is to be recorded with regret that a certain

class of tourists, to whom nothing is

sacred, had commenced to strip and carry away pieces of the bark from this

tree, and so came the necessity for a notice-board and tree-guard, in

themselves a witness against the relic hunting vandal who lightly destroys what

can never be replaced. Even Livingstone, the discoverer of the Falls, excuses

himself for ‘this piece of vanity.’ Would that others were only as sensitive on

this point as the great explorer, and delay carving their meaningless initials

on the trunks of trees until they can boast such a world-wide fame as was his

to excuse the act!” (Sykes, 1905)

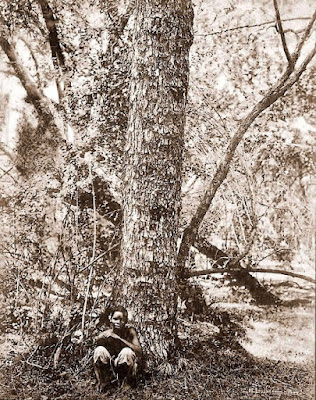

The Livingstone Name Tree (Image from early postcar)

The railway line from

the south to the Victoria Falls was completed

in April 1904, and soon after, in June, the Victoria Falls Hotel opened its

doors to its first guests. Construction of the Victoria Falls Bridge

started later the same year, with the official opening held in September 1905.

Tours to Livingstone Island,

and a visit to the 'Livingstone Name Tree,' were a key part of a visit to the

Falls for early visitors. In January 1906, however, it was reported that there

were fears tree was dying.

"The Livingstone

correspondent of the Bulawayo Chronicle states that the tree upon which Dr

Livingstone carved his initials at the Victoria Falls, is dying, and it is

proposed to cut down the trunk and send it to London to be preserved with other relics. It

is further proposed to perpetuate the memory of the great explorer by erecting

a monument on the spot where the tree now stands.” (News from Barotsiland,

1906)

When the now famous bronze

statue of David Livingstone was unveiled overlooking the western view of the

Falls in August 1934, news reports recorded Livingstone’s initials were

apparently still faintly visible on the tree he had originally carved them into

in 1855, although by now serious doubts were being expressed as to the

authenticity of the marks and even the identification of the tree itself.

References

Knight, E. F. (1903) South Africa

after the War, A Narrative of Recent Travel. Longmans, Green and Co, London.

Sykes, F. W. (1905)

Official Guide to the Victoria

Falls. Argus Co., Bulawayo.

News

from Barotsiland (1906) No.27, January 1906. p.8.

- - -

Cataract Island Under Threat of Tourism Development

The sacred island

sanctuary and protected wildlife refuge of Cataract Island is threatened by the

recent launch of tourism tours and activities to the island, endangering not

only its fragile ecology but also the wider status of the Falls as a World

Heritage Site.

Read more: Fears Grow

Over Falls

World Heritage Status

- - -

Peter Roberts is an ecologist, conservationist and

freelance researcher and writer with a special focus on the Victoria

Falls region. He is author of several books on the history of the

Falls, including 'Footsteps Through Time - a history of Travel and Tourism to the

Victoria Falls' [First published in July 2017, revised third edition April

2021].